“In addition to those wide paths in the forest, there are smaller ones, ones that are smaller still, and the very smallest ones. Some are used by game animals, some by mice for example, and some perchance by ants. The size of the world you experience depends on how big you yourself are.” (1)

Through his oeuvre, the Czech artist Lubo Kristek (born 8 May 1943) has become part of the broader movement of European postmodern culture. His works are characterised by kaleidoscopic multi-layered nature, artistic playfulness, interpretative plurality and fractality. Kristek’s artistic and craft skills oscillate between painting, assemblage, wood carving, sculptures and happenings. Kristek’s cosmopolitan aspects of work and the ability to apply transcultural experience are linked with his emigration to West Germany in 1968. After this, Kristek also travelled around the United States and visited various cultural sites in Europe. Kristek is an artist and creator within whom diverse cultural elements and configurations are integrated archetypally and due to the influence of his own personal life experiences, elements and configuration which run through his works.

Through his oeuvre, the Czech artist Lubo Kristek (born 8 May 1943) has become part of the broader movement of European postmodern culture. His works are characterised by kaleidoscopic multi-layered nature, artistic playfulness, interpretative plurality and fractality. Kristek’s artistic and craft skills oscillate between painting, assemblage, wood carving, sculptures and happenings. Kristek’s cosmopolitan aspects of work and the ability to apply transcultural experience are linked with his emigration to West Germany in 1968. After this, Kristek also travelled around the United States and visited various cultural sites in Europe. Kristek is an artist and creator within whom diverse cultural elements and configurations are integrated archetypally and due to the influence of his own personal life experiences, elements and configuration which run through his works.

We can see the influence of the art of natural peoples in his assemblages and sculptures from the end of the sixties / start of the seventies. The native art of Africa and Polynesia, and the culture of American Indians and pre-Columbian America resonate in the individual artefacts. For example, Kristek’s assemblage Expecting (1969) represents a type of personal fetish which its creator has endowed with supernatural abilities and properties. But it may also be an artistic objectification of the human ability to accept life changes and influence fate. Every fetish concentrates a certain energy, which can be used in one’s own favour and for one’s own protection. One part of the fetish is the receptacles concealed in the stomach in which magical items are placed.(2) The assemblage Expecting has the expressive form of a female figure with the mouth opened wide for a desperate scream. Below her full breasts bulges a large stomach, where Kristek has added the symbol of faith, Christ nailed to the cross, to her navel. Kristek burned the surface of the assemblage with a flame, which is why part of Christ’s body is missing, but he painted it in.(3) This assemblage was a forerunner of his further artistic development, because a fetish can also be a fixed object – a spring, a cave or a tree. In the assemblage The Flyer (1969), Kristek created the shape of a female body with a head reminiscent of a bird's beak.(4) The assemblage develops the theme of the moai tangata manu wooden sculptures, which were created on Easter Island and which are associated with the Birdman cult.(5)

We can see the influence of the art of natural peoples in his assemblages and sculptures from the end of the sixties / start of the seventies. The native art of Africa and Polynesia, and the culture of American Indians and pre-Columbian America resonate in the individual artefacts. For example, Kristek’s assemblage Expecting (1969) represents a type of personal fetish which its creator has endowed with supernatural abilities and properties. But it may also be an artistic objectification of the human ability to accept life changes and influence fate. Every fetish concentrates a certain energy, which can be used in one’s own favour and for one’s own protection. One part of the fetish is the receptacles concealed in the stomach in which magical items are placed.(2) The assemblage Expecting has the expressive form of a female figure with the mouth opened wide for a desperate scream. Below her full breasts bulges a large stomach, where Kristek has added the symbol of faith, Christ nailed to the cross, to her navel. Kristek burned the surface of the assemblage with a flame, which is why part of Christ’s body is missing, but he painted it in.(3) This assemblage was a forerunner of his further artistic development, because a fetish can also be a fixed object – a spring, a cave or a tree. In the assemblage The Flyer (1969), Kristek created the shape of a female body with a head reminiscent of a bird's beak.(4) The assemblage develops the theme of the moai tangata manu wooden sculptures, which were created on Easter Island and which are associated with the Birdman cult.(5)  The sculptures consist of a human face and the head of a frigate bird transforming into a beak. The arms are held tightly beside the body.(6) Kristek wrapped ropes around the assemblage, which has no feet. The protruding ribs and spine, and the leaning position of the skinny body imbue the moai tangata manu sculptures with an existential dimension. This kind of physiognomy also permeates Kristek’s sculpture Life (today the third station of Kristek Thaya Glyptotheque)(7). The human forms in the sculpture Life intermingle with animal elements and include the forms of embryos. He also worked with the motif of human embryos in the sculpture Atom and People (1971), where they form the bushy crown of a tree.(8) A special position in Kristek’s work is occupied by the motif of the broken sphere, which he used in the wooden sculpture The Death of Arno Lehmann (1973), created as a homage to his deceased teacher, the Austrian artist Arno Lehmann (1905–1973)(9). On the basis of their discussion, the archetypal vision of the sphere took shape in Kristek’s imagination, a form which he saw as an absolute shape containing the greatest concentration of energy. The totem poles of the North American Indians also influenced the form of his sculptures. Kristek also used the motif of the sphere(10) in the sculpture Thaya – Destiny of a Tree (today the fifth station of Kristek Thaya Glyptotheque).(11) However, the bottom line of this sculpture is augmented with the motif of skulls, referencing the South American Paracas culture.(12)

The sculptures consist of a human face and the head of a frigate bird transforming into a beak. The arms are held tightly beside the body.(6) Kristek wrapped ropes around the assemblage, which has no feet. The protruding ribs and spine, and the leaning position of the skinny body imbue the moai tangata manu sculptures with an existential dimension. This kind of physiognomy also permeates Kristek’s sculpture Life (today the third station of Kristek Thaya Glyptotheque)(7). The human forms in the sculpture Life intermingle with animal elements and include the forms of embryos. He also worked with the motif of human embryos in the sculpture Atom and People (1971), where they form the bushy crown of a tree.(8) A special position in Kristek’s work is occupied by the motif of the broken sphere, which he used in the wooden sculpture The Death of Arno Lehmann (1973), created as a homage to his deceased teacher, the Austrian artist Arno Lehmann (1905–1973)(9). On the basis of their discussion, the archetypal vision of the sphere took shape in Kristek’s imagination, a form which he saw as an absolute shape containing the greatest concentration of energy. The totem poles of the North American Indians also influenced the form of his sculptures. Kristek also used the motif of the sphere(10) in the sculpture Thaya – Destiny of a Tree (today the fifth station of Kristek Thaya Glyptotheque).(11) However, the bottom line of this sculpture is augmented with the motif of skulls, referencing the South American Paracas culture.(12)

Over the course of his life, Kristek has visited various places around the world. He enjoyed wandering through the landscape and tried to discover and understand its essence, as he did with its inhabitants and their way of life. These were trips, drifting and wandering which had an inner meaning for his life and work, because when wandering through an alien landscape and culture one can free oneself of the things one knows or feels that one knows about the world in advance. All of a sudden, people can perceive things and phenomena in the present and existentially enhanced moment. In this way Kristek returned to the prototype of the man who strode through the landscape, had an opportunity to stop and think, and who left his own trace and imprint on it.

Over the course of his life, Kristek has visited various places around the world. He enjoyed wandering through the landscape and tried to discover and understand its essence, as he did with its inhabitants and their way of life. These were trips, drifting and wandering which had an inner meaning for his life and work, because when wandering through an alien landscape and culture one can free oneself of the things one knows or feels that one knows about the world in advance. All of a sudden, people can perceive things and phenomena in the present and existentially enhanced moment. In this way Kristek returned to the prototype of the man who strode through the landscape, had an opportunity to stop and think, and who left his own trace and imprint on it.

“People carry their own internal vision of the landscape with them which says that landscape should be reshaped. So the logical consequence of the internal landscape in each one of us is a belief that in the landscape we have to constantly come across the footprints of a culture, the footprints of our ancestors and our own footprints.” (13)

Kristek has left his artistic footprint in the landscape on the coast of Cantabria. It is the assemblage Barbed Wire of Christ (1983), the metal body of which is a pitiful relic of the current mechanised, dehumanised, rationalised world.

Some time later, in 1986, he created the assemblage Sea Horse on the Italian coast. This wooden figure of a horse with a skull instead of a head, and with clumps of rope representing the mane and tail, is a symbol of life in motion and the galloping waves of the sea. The horse here becomes the guide on the journey through this life and to the next one. Kristek’s sculptures confirm that landscape represents the result of human re-shaping and co-creation. And so the work of art in the landscape becomes its mirror.(14)

Some time later, in 1986, he created the assemblage Sea Horse on the Italian coast. This wooden figure of a horse with a skull instead of a head, and with clumps of rope representing the mane and tail, is a symbol of life in motion and the galloping waves of the sea. The horse here becomes the guide on the journey through this life and to the next one. Kristek’s sculptures confirm that landscape represents the result of human re-shaping and co-creation. And so the work of art in the landscape becomes its mirror.(14)

The first sculptures in the landscape were forerunners of Kristek’s magnum opus, the Thaya Glyptotheque. The sculptural pilgrims’ way along the river Thaya was created in the years 2005 to 2006. The trail on which Kristek located his artworks runs through the Czech Republic, Austria and Slovakia. It consists of eleven symbolic stations – a gallery in the landscape and a pilgrimage route made up of new artefacts created for a specific space or Kristek’s older works. The artworks in various places fulfil a whole range of functions, from acting on the viewer in the form of preparation for the spiritual climax of the pilgrimage, to the role of a focal point indicating and emphasising the place of a spiritual, philosophical or artistic act. The individual stations can be perceived by walking, which creates a relationship between the places, by the pilgrim discovering them. Wandering from one station to the next gives them an additional dimension to contrast with the predominant consumer lifestyle of our society. The pilgrimage here becomes a “ritual of purging, an act of humility, a rejection of the pride of reason.” (15) Kristek Thaya Glyptotheque is a creative projection of the human relationship with the river Thaya. The cult of water in our country is of Indo-European origin and is linked with fertility and healing. The cult of miraculous wells and springs as a trait of “pagan Christianity” was characteristic of the Baroque era in particular, when processions were held to some wells. The cult of water is expressed through human activities and the way that revered places are treated.(16) This tradition is also revived through artistic resources in Kristek Thaya Glyptotheque, where meetings and happenings occur at the individual stations. With the Thaya Glyptotheque, Kristek participates in the activation and creation of a space in which there is an oscillation of nature and culture in the broader geographical, historical and social context.(17) Every place which has been interpreted through human intervention gains an idea and genius loci. The genius loci is the spirit of the landscape and the means of viewing the landscape. The genius loci is the unnameable cause for which we return to a given place.(18)

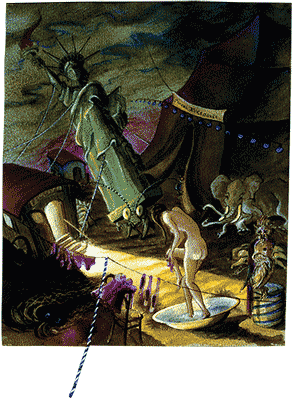

In 1971, Kristek initiated the tradition of night vernissages(19), which currently represent the start of happenings. His happenings represent an allusion to the grand baroque theatrical productions where “the king danced” before his courtiers. The production was accompanied by floats and entourages. After the parade of floats had passed, singers performed and there was a dressage, where the king also performed. The musical-dance performance was accompanied by impressive narration intended to dazzle the watching audience. The active participation of the king at the grand productions of the court theatre had great social value, and symbolised and confirmed his important status in society.(20) And during Kristek’s happenings the king performs too, this being Kristek himself, viewing the spectacle of colours, sounds, shadows and the tangle of human bodies. In the happening Mythological Landscape No. 94 – A Cart Full of Tones(21) Kristek was brought in on a cart.(22)

Video: happening A Cart Full of Tones

(30th July 1994, Podhradí nad Dyjí)

Another happening, Mythological Landscape No. 96 – The Burial of the Seven-Sin Heritage or Where Evrum is Born(23), involves a baroque hearse pulled by a team of six Kladruby horses, evocative of the winged Pegasus. During the happening, a cortege of beings on stilts creeps along the side of the graveyard, and all of a sudden bodies come to life in the graveyard and start to dance. The baroque tendency here is characterised by the liking for movement and courageous “twisting of figures”. The appearance of Kristek from a grave also underlines the public baroque death and its theatricality. In his happenings Kristek attacks the viewers’ senses with wonderful narrative scenes, lighting, changes in scenery, elaborate costumes, water effects, floating, birth and appearance of people.(24)

Video: happening The Burial of the Seven-Sin Heritage or Where Evrum is Born

(27th July 1996, Podhradí nad Dyjí)

The happening The Phylogenetic Very Wet Wedding or How the Weary World of People Return to the Watery Depths also occurred in costume on a backwater of the river Thaya. During another happening, Mythological Landscape No. 95 in Three Acts (25), Kristek opened the forest chapel Nympheum Chapelle dela Surae, the guardian of which is the nymph Thaya.(26)

Video: happening Mythological Landscape No. 95 in Three Acts

(8th August 1995, Podhradí nad Dyjí)

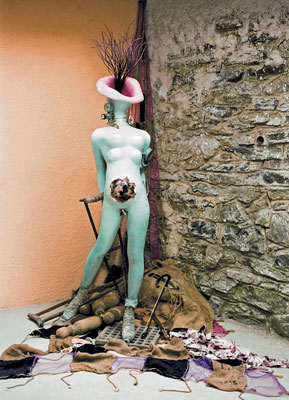

Kristek’s happenings are infused with the motif of death, monstrosity and sickness, generally counterbalanced by the principles of birth, emergence and resurrection. The happening Kristek’s Touch 2013(27) features the main figure of an obese, vulgar naked woman, drawing attention to the hedonistic gluttony and greed becoming the lifestyles in the postmodern era. Hedonism is associated with consumption, based on the idea of immediate satisfaction of all material needs at the expense of cultural values.(28) A dead cow became a part of the happening Pyramidae – Klipteon II or Mythological Landscape No. 2002(29). A sacred cow with a polythene mummy located in its stomach arrived on a cart. Kristek emerged from the amniotic sac wearing a loincloth.(30)

Video: happening Pyramidae – Klipteon II

(1st June 2002, Podhradí nad Dyjí)

Through this happening Kristek identified himself with the artistic techniques of the contemporary postmodern artists represented by the British artist Damien Hirst (born 1965)(31). In his work, a fascination with death and ugliness becomes an artistic means of renewing aesthetic perception. Kristek’s shocking spectacle turns that which was formerly considered ugly or even grotesque into a new type of beauty. The important thing is to make the viewer and participant think about and re-evaluate consumer values. His happenings provoke discussion and force the audience to adopt an attitude, or at least stop and think about the problems of mass society and standardised pop cultures.

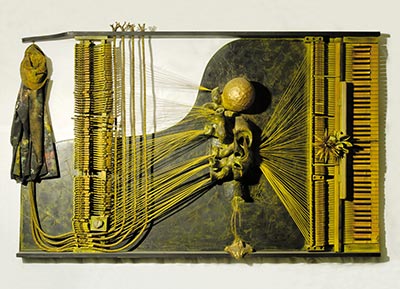

Kristek transforms the assemblage into modern types of altars and tabernacles. The assemblages are distinguished by an exceeding of the concept of the paiting and the frame. Through his assemblages, Kristek creates a platform from which he can escape from the strictly prescribed space or go beyond material or other objects. Just as with other works, the assemblages generally bear the designators of the psychoanalytic dictionary, but they also include hidden archetypal patterns and ideas. Kristek’s assemblages speak for themselves and are truthful about themselves. “No archetype can be reduced to a simple formula. It is a vessel which we can never empty or fill completely (…)”.(32) In a comparable manner, music can also have a different message and require a special hearing. He has incorporated musical instruments or strings into several assemblages, for example On the Landfill of Ages (1994) and Metastation of Abandoned Tones (1975−1976).(33) His greatest artistic object is the grand piano located in the course of the happening A Cart Full of Tones(34) of 1994 on the roof of his painting studio in Podhradí nad Dyjí.(35)

Kristek transforms the assemblage into modern types of altars and tabernacles. The assemblages are distinguished by an exceeding of the concept of the paiting and the frame. Through his assemblages, Kristek creates a platform from which he can escape from the strictly prescribed space or go beyond material or other objects. Just as with other works, the assemblages generally bear the designators of the psychoanalytic dictionary, but they also include hidden archetypal patterns and ideas. Kristek’s assemblages speak for themselves and are truthful about themselves. “No archetype can be reduced to a simple formula. It is a vessel which we can never empty or fill completely (…)”.(32) In a comparable manner, music can also have a different message and require a special hearing. He has incorporated musical instruments or strings into several assemblages, for example On the Landfill of Ages (1994) and Metastation of Abandoned Tones (1975−1976).(33) His greatest artistic object is the grand piano located in the course of the happening A Cart Full of Tones(34) of 1994 on the roof of his painting studio in Podhradí nad Dyjí.(35)

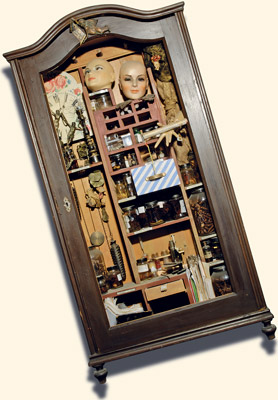

In the same way as other foreign postmodern artists, through the technique of assemblage, Kristek has deconstructed  and artistically reinterpreted the postmodern situation of man in the “fluid” era of globalisation. In the assemblage Arachnológia adè (2000), Kristek followed on from the boxes (microcosms) of the American artist Joseph Cornell (1903–1972); in the assemblage Bed (2000), he referenced the anonymous figurines of the American sculptor Edward Kienholz (1927–1994), and in the assemblage In the Prematurely Cloned Age of One Planet (2003), he followed on from the work of the Italian artist Michelangelo Pistoletto (born 1933). In 2007, Kristek presented the form of interactive assemblage, when he created the work Requiem for Mobile Telephones from a collection of mobile telephones.(36)

and artistically reinterpreted the postmodern situation of man in the “fluid” era of globalisation. In the assemblage Arachnológia adè (2000), Kristek followed on from the boxes (microcosms) of the American artist Joseph Cornell (1903–1972); in the assemblage Bed (2000), he referenced the anonymous figurines of the American sculptor Edward Kienholz (1927–1994), and in the assemblage In the Prematurely Cloned Age of One Planet (2003), he followed on from the work of the Italian artist Michelangelo Pistoletto (born 1933). In 2007, Kristek presented the form of interactive assemblage, when he created the work Requiem for Mobile Telephones from a collection of mobile telephones.(36)

Many artists in the 1950s and 1960s used fire as a means of expression. Some of them implemented installations and then photographed or filmed them (Eduard Ovčáček or Zorka Ságlová), others painted with flame (Yves Klein, Jiří Georg Dokoupil or Ladislav Novák), created collages (Eduard Ovčáček or Věra Janoušková) or used fire to create sculptures and objects (Jan Koblasa or Eduard Ovčáček). The French artist Yves Klein “burnt” paintings and drawings on to card using a naked flame.(37)  Fire became an active medium in the work of the German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer (born 1945), who considers it a symbol of destruction and birth.(38) Kristek started to experiment with fire at the end of the 60s and start of the 70s, when he modelled wood using flame and in this way altered its specific structure. His experiments resulted in wooden sculptures which he either burnt just slightly or where he burnt their surface until it was completely smooth. Kristek annulled his own artistic handwriting through flame. In the wooden sculpture Soul (1973) the fineness of the burnt structure is graduated up to shine and at the same time to the colourfulness and legibility of the rings. Although Kristek interfered with and destroyed his work with fire – he cast it into a dark place out of time – he also managed to accent its new dimension. Just like the Mayans, he does not consider the form of his work to be definitive and unique. The world and the work must be destroyed so that it can be born anew and repeatedly.

Fire became an active medium in the work of the German painter and sculptor Anselm Kiefer (born 1945), who considers it a symbol of destruction and birth.(38) Kristek started to experiment with fire at the end of the 60s and start of the 70s, when he modelled wood using flame and in this way altered its specific structure. His experiments resulted in wooden sculptures which he either burnt just slightly or where he burnt their surface until it was completely smooth. Kristek annulled his own artistic handwriting through flame. In the wooden sculpture Soul (1973) the fineness of the burnt structure is graduated up to shine and at the same time to the colourfulness and legibility of the rings. Although Kristek interfered with and destroyed his work with fire – he cast it into a dark place out of time – he also managed to accent its new dimension. Just like the Mayans, he does not consider the form of his work to be definitive and unique. The world and the work must be destroyed so that it can be born anew and repeatedly.

In his work, Kristek also focussed on the nude female body, which he perceived and presented as an artistic tool and resource for an event. He updated the creative process of the French artist Yves Klein (1928−1962), who in 1958 started to use a naked female body instead of a brush. Later Klein started to add performance accompanied by music to his method of painting.(39) One can perceive Kristek’s first intimation of bodypainting in the happening The Parting of Lubo Kristek with Salvador Dalí, implemented in 1989 in Kempten, Germany. Kristek wrote Adé Dalí on the stomach of a nude model as an artistic way of expressing respect for his role model and teacher, the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí (1904–1989). In 1995, this was followed by the bodypainting event in Landsberg called The Crucifixion of Sybil(40). Kristek covered the naked body – the living brush – in paint and printed it on to a prepared canvas. In regard to the female body, Kristek’s work was a continuation of the highly expressive baroque-like variants of the crucified female nude. The Belgian painter Félicien Rops (1833–1898)(41), the Czech photographer František Drtikol (1883−1961)(42) and the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan (born 1960)(43) had previously dealt with this theme in their works. Kristek depicted a crucified woman in 1996 on the painting First Phase of the Birth of Eroticism Coming from an Unknown Thorn. The beauty and grace of the female body outshone and replaced the motif of the Crucified Christ. The combination of Crucified female and Crucified male occurred in the happening The Conception with Time or Sarcophagus of Dreams(44).(45) In a similar way, Kristek used the motif of a woman lying at the foot of the cross and dressed as a ballet dancer on the painting On the Edge of Frivolous Society (2002), which is a variant and persiflage on the penitent Mary Magdalene. But Christ on the cross is replaced by a deformed musical instrument.(46) On many of Kristek’s paintings an expressively elaborated form of symbolism has matured in which the emphasis is placed on every element of the composition. Nothing here appears by accident, and everything is subject to hidden contents. The work of art expresses the inner psychological states and intensifies their expression with an exaggeration of colour and shape or deformation.

In his work, Kristek also focussed on the nude female body, which he perceived and presented as an artistic tool and resource for an event. He updated the creative process of the French artist Yves Klein (1928−1962), who in 1958 started to use a naked female body instead of a brush. Later Klein started to add performance accompanied by music to his method of painting.(39) One can perceive Kristek’s first intimation of bodypainting in the happening The Parting of Lubo Kristek with Salvador Dalí, implemented in 1989 in Kempten, Germany. Kristek wrote Adé Dalí on the stomach of a nude model as an artistic way of expressing respect for his role model and teacher, the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí (1904–1989). In 1995, this was followed by the bodypainting event in Landsberg called The Crucifixion of Sybil(40). Kristek covered the naked body – the living brush – in paint and printed it on to a prepared canvas. In regard to the female body, Kristek’s work was a continuation of the highly expressive baroque-like variants of the crucified female nude. The Belgian painter Félicien Rops (1833–1898)(41), the Czech photographer František Drtikol (1883−1961)(42) and the Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan (born 1960)(43) had previously dealt with this theme in their works. Kristek depicted a crucified woman in 1996 on the painting First Phase of the Birth of Eroticism Coming from an Unknown Thorn. The beauty and grace of the female body outshone and replaced the motif of the Crucified Christ. The combination of Crucified female and Crucified male occurred in the happening The Conception with Time or Sarcophagus of Dreams(44).(45) In a similar way, Kristek used the motif of a woman lying at the foot of the cross and dressed as a ballet dancer on the painting On the Edge of Frivolous Society (2002), which is a variant and persiflage on the penitent Mary Magdalene. But Christ on the cross is replaced by a deformed musical instrument.(46) On many of Kristek’s paintings an expressively elaborated form of symbolism has matured in which the emphasis is placed on every element of the composition. Nothing here appears by accident, and everything is subject to hidden contents. The work of art expresses the inner psychological states and intensifies their expression with an exaggeration of colour and shape or deformation.

One can describe the ballerina and the dancer, indulging in movement, as the central theme of Kristek’s work. This form of dynamism has probably shifted Kristek’s work from artistic creation to happenings, which are also infused with the character of the ballerina. Kristek also painted the ballerina and dancer on the canvases Billiards for Life and the Ballerina (1987), … and the Swans Flew Away Too (1989) and Breezy Courtship in the Bird Space (2002).(47) Their movements can be described as a long, living ribbon via which rapid waves run. The ballerinas turn, transform or float. Here Kristek is following on from the dynamic dancer theme of the French painter Edgar Degas (1834–1917), who painted the graceful silhouettes of ballerinas and dancers during moments of exhaustion and rest, exertion and strain. He was fascinated by movement, movement drilled through hard training.(48) “The movements of dancers, however varied, are governed by a strict code, they are

One can describe the ballerina and the dancer, indulging in movement, as the central theme of Kristek’s work. This form of dynamism has probably shifted Kristek’s work from artistic creation to happenings, which are also infused with the character of the ballerina. Kristek also painted the ballerina and dancer on the canvases Billiards for Life and the Ballerina (1987), … and the Swans Flew Away Too (1989) and Breezy Courtship in the Bird Space (2002).(47) Their movements can be described as a long, living ribbon via which rapid waves run. The ballerinas turn, transform or float. Here Kristek is following on from the dynamic dancer theme of the French painter Edgar Degas (1834–1917), who painted the graceful silhouettes of ballerinas and dancers during moments of exhaustion and rest, exertion and strain. He was fascinated by movement, movement drilled through hard training.(48) “The movements of dancers, however varied, are governed by a strict code, they are  movements within constant patterns.” (49)

movements within constant patterns.” (49)

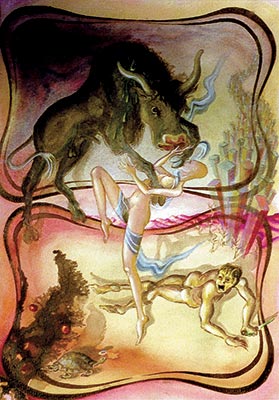

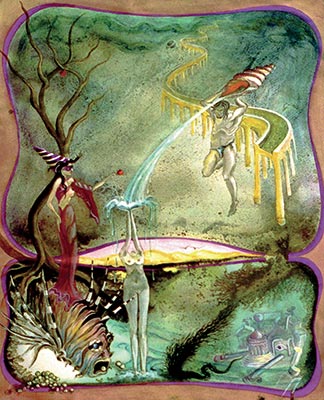

Kristek’s ballerinas resonate with the ideal of dynamic motivity and movement. For his ballerinas neither the floor nor the boards existed, just an environment which adapts itself and at the same time becomes a world of constant metamorphosis. Neither is there anything stable or rigid in their bodies, no identifiable bones or joints. In a manner similar to Degas, Kristek also seeks inspiration in Greek and Roman mythology. “In answer to the question as to what made him interested in ballet, Degas answered that in it he discovered the reanimated movements of the Greeks.” (50) But Kristek’s dancers gradually acquire the form of Greek and Roman mythological beings, for example Pasiphaë, the wife of the Cretan king Minos, on the painting Pasiphaë through the Eyes of the Modern Era and Average Sodomising Moment (1994). Kristek also focussed on the goddess Venus and variant of her birth  in the painting Cosmo-Lactic Connections between the Extinct World of Atlantis, Rare Liquid from the Holy Scallop and My Fortune Teller – Viola Laluleilá (1994).

in the painting Cosmo-Lactic Connections between the Extinct World of Atlantis, Rare Liquid from the Holy Scallop and My Fortune Teller – Viola Laluleilá (1994).

Kristek presents a modern, new type of Venus in the work The Dancer’s Evening Toilet (1991). He painted the woman standing in a tub of water – a modern version of the shell. He turned the female body to present the buttocks, whereby he attained a change in the point of view because the breasts, stomach and loins are hidden from the viewer. He also transposed the world of the theatre and its characters into the form of goddesses or demigoddesses. Nymphs, sirens and naiads are located on the shoreline in Kristek’s painting Two Female Clowns (1987)(51), evocative of the work of the Czech painter Beneš Knüpfer (1844–1910).(52)

Kristek’s craft skill is employed to the greatest extent in metal sculptures, where he utilises his perfect mastery of the technique of the German artist Max Doerner (1870–1939). Just like a medieval artist, Kristek personally welds, grinds and carves his sculptures. From many aspects his free-standing sculptures represent a surreal parallel with the paintings of the Czech painter Mikuláš Medek (1926–1974), the German painter Max Ernst (1891–1976) and the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí. This is documented in particular by Kristek’s metal sculptures Monument to the Five Senses (1991) and Tree of the Aeolian Harp (1992). In dreamlike and fantasy themes, Kristek puts the creative aspect of a Freudian world of unconscious and concrete irrationality(53) into direct opposition with the one-sided, rational, usual and conventional world. Kristek also complies with the basic principle of surrealism – the principle of spontaneous creation of the shape from chaos in which he listens to the stimuli linking man with nature. Kristek opens the gates to mental and natural underground resources.(54) In his artistic work, there appear a certain unpredictability and seismic activity which allow him to escape from the controlled space. Kristek follows the idea of a total work of art, so-called Gesamtkunstwerk.

Kristek’s craft skill is employed to the greatest extent in metal sculptures, where he utilises his perfect mastery of the technique of the German artist Max Doerner (1870–1939). Just like a medieval artist, Kristek personally welds, grinds and carves his sculptures. From many aspects his free-standing sculptures represent a surreal parallel with the paintings of the Czech painter Mikuláš Medek (1926–1974), the German painter Max Ernst (1891–1976) and the Spanish painter Salvador Dalí. This is documented in particular by Kristek’s metal sculptures Monument to the Five Senses (1991) and Tree of the Aeolian Harp (1992). In dreamlike and fantasy themes, Kristek puts the creative aspect of a Freudian world of unconscious and concrete irrationality(53) into direct opposition with the one-sided, rational, usual and conventional world. Kristek also complies with the basic principle of surrealism – the principle of spontaneous creation of the shape from chaos in which he listens to the stimuli linking man with nature. Kristek opens the gates to mental and natural underground resources.(54) In his artistic work, there appear a certain unpredictability and seismic activity which allow him to escape from the controlled space. Kristek follows the idea of a total work of art, so-called Gesamtkunstwerk.  His work combines all the artistic types in a single whole, which culminates in the Chateau Lubo in Podhradí nad Dyjí – in Kristek’s Valley of Divine Ephemerality of Tone – where he settled after returning from emigration after 1989 and where he carries out his artistic activity to this day.

His work combines all the artistic types in a single whole, which culminates in the Chateau Lubo in Podhradí nad Dyjí – in Kristek’s Valley of Divine Ephemerality of Tone – where he settled after returning from emigration after 1989 and where he carries out his artistic activity to this day.

Text: Barbora Půtová

Stations of the Glyptotheque: Introduction